How Nora Daza won over the French with calderetta, taba ng talangka and capiz chandeliers

That message struck me because I never thought of it that way – but now that I am piecing parts of her life together, I realize how true that sentiment was. That perhaps indirectly, Nora Daza did devote most of her culinary life to the Filipinos, for the Filipinos, here and abroad.

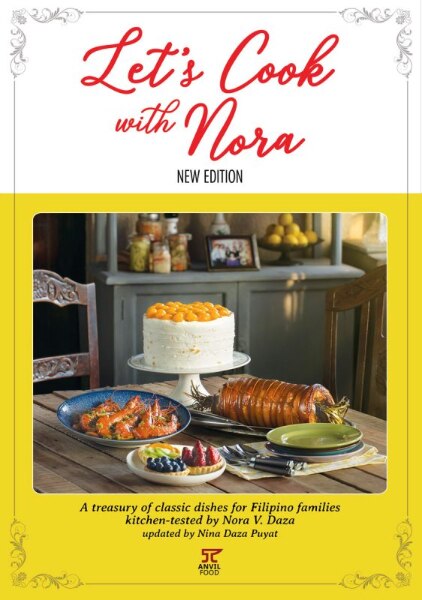

The name Nora Daza is synonymous to food. And that’s because many people associate her name with the cooking show on TV “Cooking It up with Nora” and her iconic cookbook Let’s Cook with Nora, first published in 1965 and then in 1969–which became the more popular edition, the one with the familiar white and yellow cover and the red letters in script.

That little cookbook proved to be a bestseller with Filipino home cooks in the ‘60s, ‘70s, all the way up to the ‘90s and even up to the early 2000s. That’s over 50 years of two or three generations of Filipinos relying on Nora Daza’s recipes.

Why was it so successful? I think it was because Nora Daza had a keen sense of what a typical Filipino family would consider a satisfying meal. She knew that as rice eaters, there had to be viands or “ulam” – a rotating cycle of two or three main dishes of chicken, beef, pork, fish, shellfish and vegetables. She knew that the average home would alternate between Pinoy dishes one day, Chinese or Chinoy dishes the next, and occasionally something American like meatloaf, or perhaps “Italian” like spaghetti or lasagna. That’s why on the cover of the cookbook, it reads: “Let’s Cook with Nora: A Treasury of Filipino, Chinese and European dishes compiled and kitchen-tested by Nora V. Daza.”

Kitchen-testing

Kitchen testing was very important to her for she knew the value of a good, reliable recipe. She carefully selected and tested the 275 recipes in the original “Let’s Cook with Nora.” Some came from her own personal collection of favorite recipes, some from the Manila Gas Cooking School (of which she was the directress in the ‘60s) and some of them culled from her two-year stay in the US, specifically at Cornell University where she earned her Master’s Degree in Restaurant Management.

The cookbook was an extensive mix of everyday fare, as well as special-occasion dishes. Leafing through the original book, you will find a very “old school” kind of layout (compared to today’s sleek and glossy cookbooks), but the recipes are timeless. Best of all, she made sure that the ingredients were accessible, and the procedures easy to follow. To those people who confessed that they didn’t know how to cook, she would simply say: Just follow my cookbook and you’ll learn.

You have to remember that this was in the 1960s when life in the Philippines was very simple. White bread, softdrinks and canned goods were all the rage – that’s why many of the recipes called for sliced white bread, evaporated and condensed milk, canned pineapple, and even canned cheese!

When women got married in those days, they became housewives or had a career but they still had to take care of the family. They either learned how to cook or they hired a helper or maid to do the cooking. And that’s how hundreds and then thousands of women came to rely on “Let’s Cook with Nora,” and learned to trust the woman behind it.

They also saw her on TV, always glammed up while cooking—with her pearls and signature coiffure. I know she did that to push the idea that cooking for the family can and should be enjoyable and gratifying —not regarded as a dreadful chore. She wanted to uplift these women and encourage them to take pride in their roles as homemakers.

Restaurants

Years after her cookbook was published, she dared to dream of bigger things. Following two trips to France – first with my Dad, Atty. Gabriel Daza Jr., the second with her sisters, she decided that she wanted to bring French cuisine to Manila.

Again, I bring you back to the time in the late 60s when there were only a few fine dining establishments in Manila. They were New Europe, Guernica’s, Vinta Grill in Sulo Makati, The Plaza, Casa Marcos, and Madrid Spanish restaurant along Highway 54, now known as EDSA.

After taking a crash course in French cuisine in Paris, she opened up Au Bon Vivant in Ermita in 1965. She also had a string of French chefs come over to live in Manila to teach our cooks (they were just called cooks then) all the authentic recipes and techniques in cooking French cuisine.

Au Bon Vivant

Designed by Architect Willy Fernandez, the husband of the late great Doreen Fernandez, the 50-seater restaurant had the ambiance of a Parisian restaurant with copper pots and pans, and French posters lining the brick walls. It had two private rooms on the second floor—named the Cornell Room and The Capricho Room.

My Mom brought in French music tapes, as well as ingredients not found in the Philippines then such as tarragon in vinegar, Dijon mustard, gruyere cheese.

She also invited a succession of French chefs to visit Manila including THE Paul Bocuse and THE pastry chef Gaston Lenôtre. How she managed to convince them to come to the Philippines in the mid-70s is still a mystery, but I know that that DINNER OF THE CENTURY (held at Au Bon Vivant in Makati) was one that Manila’s elite will never forget.

Thus began her life as a restaurateur and she opened up more restaurants one after the other. Aux Iles Philippines in Paris in 1972, Au Bon Vivant Makati in 1974, Maharlika at the Philippine Center in New York in 1975, Au Bon Vivant Quezon City in 1976, Galing Galing Filipino restaurant in Ermita in 1977.

Nora Daza became a pioneer in showcasing Philippine cuisine abroad—in Paris via Aux Iles Philippines for 11 years, from 1972 to 1983, and then it reopened in 1995, staying in business up to 1999; and then in New York City via Maharlika for about 4 years, from 1975 up to 1977.

I never had the opportunity to visit Maharlika (I was still in grade school) but I did get to spend summers in Paris working at our Aux Iles Philippines as a waitress, cashier, bartender – as did my siblings Bong, Sandy, Mariles and Stella, and we saw firsthand how our mother Nora Daza became the unofficial culinary ambassadress of the Philippines to France. Again, this was Paris in the early 70s and the French knew next to nothing about the Philippines. Their only exposure to Asian cuisine was via the small Vietnamese, Chinese restaurants, and a few Japanese and Korean restaurants around Paris.

She was determined to educate the French about the Philippines and Filipino culture, through food. She believed that Filipino dishes could stand proudly beside other Asian cuisines particularly because we had a curious mix of Spanish, Chinese and American influences in our food.

Even the actual restaurant had to elegant and impressive - a showcase of the best of the Philippines. Many of our customers were impressed as soon as they walked into Aux Iles Philippines with its brass and capiz chandeliers, lacquered capiz placemats and candle holders, green and yellow tablecloths. Filipino music was always playing in the background, and our waiters proudly wore the barong Tagalog.

Nora Daza always took the time to engage the customers in conversation, ready to tell them all about the Philippines. She trained our waitstaff (including us siblings) to explain to curious diners things like why we had tomato sauce in our calderetta (the Spanish influence), or why we had pancit guisado on our menu (the Chinese influence).

The French were blown away by the flavor of our taba ng talangka. Ordered from Pampanga, these precious cans were packed into her luggage bound for Paris. This baby crab fat sauce was served over steamed prawns – and the customers loved it especially when they learned that taba ng talangka was collected drop by drop from tiny little crabs.

At the restaurant, we kept coffee table books about the Philippines ready for customers to browse. Many of them wanted to know what ube or langka or macapuno looked like. We offered desserts like Ube Pie, Langka Mousse and macapuno preserves dolloped over a scoop of vanilla ice cream. We also served Sans Rival, Banana Cream Pie and Dayap Mousse. While not native Filipino desserts, Nora Daza explained that the Americans taught us Filipinos how to make cakes, cookies and pies.

Ripple effect

In one interview, I was asked if Nora Daza’s efforts had a direct impact on Filipino cuisine and my answer was this: Perhaps her two Filipino restaurants – one located in Europe and one in America - did not have a direct effect on Filipino cuisine at that time, but I’m certain that they did create a ripple effect, an effect that we still feel today.

They definitely created a ripple effect in the hearts of weary Filipino travelers over a span of 14 years (10 years in Rue Laplace and 4 years in Rue Pontoise) who found an oasis in Paris. Imagine Filipino tourists who, after weeks of eating bread, cheese, cold cuts, and salads — could finally dine on hot white rice and ulam — food that tasted like home. Seeing their smiles was priceless. They were always so grateful to be able to eat familiar dishes like sinigang, adobo, lechon kawali, lumpia, pancit, etc… and chat with our staff in Tagalog.

Another wave of this ripple effect would be in the minds of thousands of French nationals and other Europeans from Italy, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, who frequented the restaurant—because many were repeat and loyal customers. Having a taste of Filipino food and hospitality was an effective introduction to our culture. At the very least, it made them more aware about the Philippines. I’m sure that because of their positive dining experiences in our restaurant, many French and European customers ended up visiting the Philippines as tourists.

The Great Maya Cookfest

Nora Daza became part of a prestigious national culinary competition in the Philippines called The Great Maya Cookfest.

Held annually from 1976 up to 1990, the contest brought Nora and the competition winners to culinary exchange programs abroad. I was fortunate to have joined them in 1980, the year I graduated from high school. It was my Mom’s graduation gift to me.

At the Towngas Center in Hongkong, the Maya Cookfest winners—dressed in Filipiniana—did a cooking demonstration for the Hongkong homemakers, while Nora Daza—in a terno—spoke to the audience, annotating every step. Again, I saw her in her element, speaking so proudly about Filipino food, and it was clear to me that they made a very good impression on the foreign audience. This scenario was replicated in Bangkok and in Singapore that year, and in the other Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Japan – and once in the US - in other years.

Nora Daza and her delegation of cooking contest winners always did their best to represent the Philippines. I think it’s safe to say that this culinary competition, which lasted for 14 years, allowed Nora many opportunities to bring Filipino cuisine to different parts of the world—another ripple effect.

Nora has been named a pioneer and a trailblazer in the Philippines—with her bestselling cookbooks, successful TV shows, and her illustrious restaurant career.

If she somehow managed to empower Filipino home cooks around the world; if she happened to inspire many Filipino chefs to start their careers; if she paved the way for more Filipinos to feel proud of their country because of their cuisine, and if she somehow managed to encourage them to start a conversation about Filipino food today, then I would concede that yes, Nora Daza, did make a significant contribution to the Philippines, as a proud Filipina who dared to dream big.

[The author wrote this tribute to her mother for the recent Asian Culinary Exchange (ACE), the annual conference that brings together chefs and various food personalities in the region. The event was aired via the YouTube and Facebook channels of Asia Society Philippines. ACE was co-presented by Nespresso Philippines and McCormick Culinary. The updated edition of the book “Let’s Cook with Nora” is now available in stores.]

Photos courtesy of Metro.Style.

https://news.abs-cbn.com/ancx/food-drink/features/10/03/21/how-nora-daza-won-over-the-french-with-taba-ng-talangka

No comments:

Post a Comment